Newsletter

Tales, tangents, truths from a brain on fire.

One email per week. No spam. No mercy.

{module title="AcyMailing subscription form"}

Cultural Mirrors

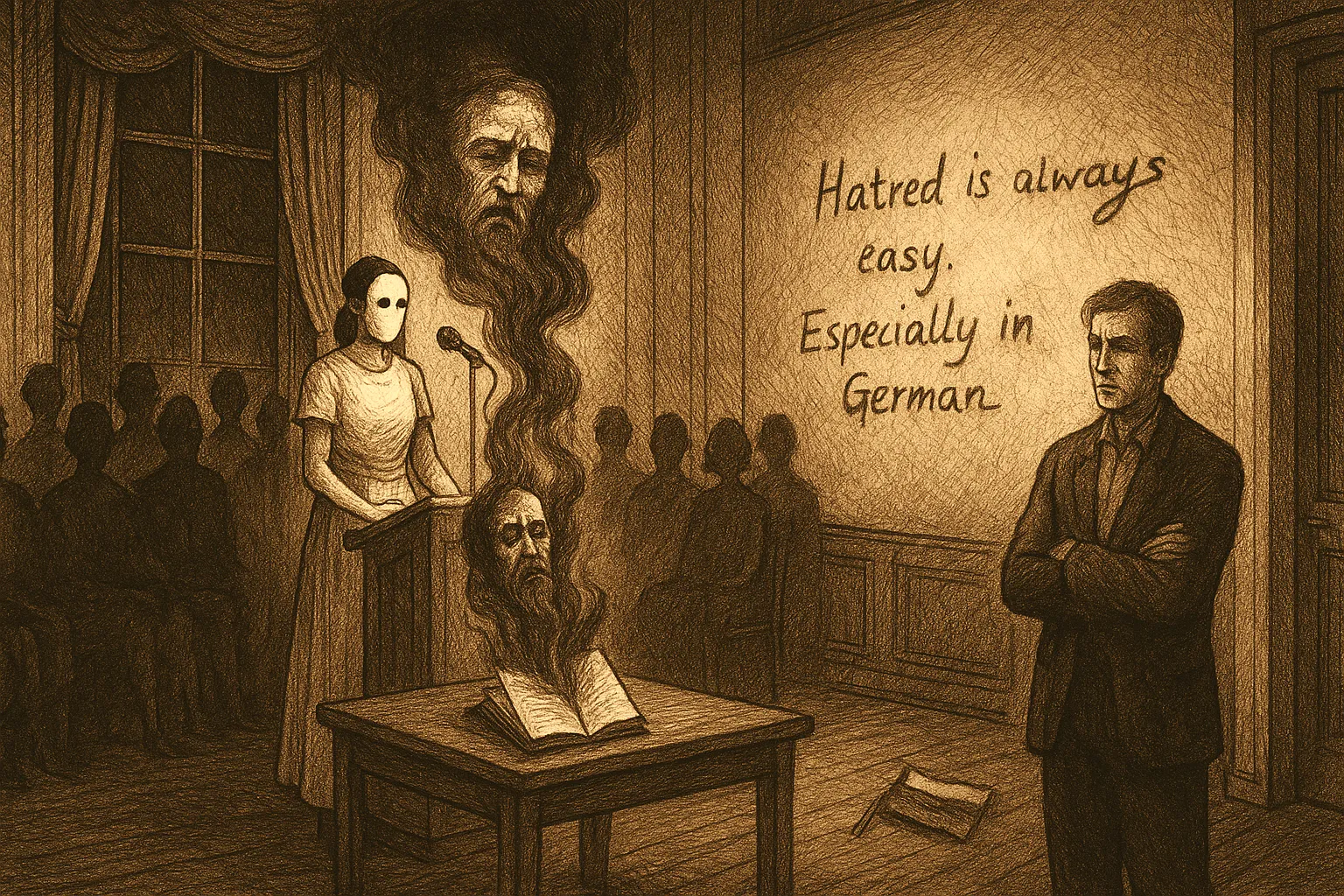

On the Unbearable Lightness of Hatred

I stepped into the luxurious hall with – thankfully already familiar – the sensation that I had the privilege of touching something truly cultivated, civilization in its least pretentious guise, the elevating voice of literature, that sort of thing. I’m not joking, nor do I think I’m exaggerating – the “Literary Colloquium” in Berlin is a place well known among connoisseurs, bearing the somewhat immodest, yet well-deserved label found on its own website: “one of the nerve centers of the entire German-language literary world.”

Look, I’ll drop the glittery words here, because at some point they just start to get on my nerves. Put simply: the place is fantastic, elegant, and stylish – as much as (virtually unlimited) money and cultural tradition (even more infinite when viewed through my Bulgarian eyes) can allow. The kind of tradition that still makes up around seventy percent of the curricula in most elite universities around the world. In short: the best of Germany. A place for reverence and reflection, a place to unburden, a place for pilgrimage. A temple.

I came with a fairly specific – though uncertainly achievable – goal: I wanted to meet the author who had the honor of presenting her latest novel here today, Sibylle Lewitscharoff (in German, her name is pronounced “Zibüle,” which makes me think of hyacinths, spring, and many other pleasant things that smell of youth and freshness). I had read her interview the day before in one of the Berlin newspapers, and I was a bit puzzled by the absence of that typically German politically correct veneer, the kind that almost never allows them to say anything bad about The Others – after all, they Bear the Guilt, it’s not easy for them, poor things. I had even suppressed – without much effort, as always – the slight discomfort that inevitably creeps in when someone starts speaking bluntly about my homeland, which almost always leads to unpleasant associations – either a toilet shows up, or something of the sort... I’ve grown used to not taking offence easily, for many years now. In short: I consider myself a professional Bulgarian. Not incidentally, I might add.

But this time was a bit different. The lady intrigued me in a very ticklish way – and when a woman intrigues you like that... I was dying to try and peek beneath the surface of the contempt, even hatred, that she made no attempt to hide. Why us, sweetheart? Yes, I see you carry a Bulgarian name, I can assume there’s something personal behind all this – but are you willing to speak about it without gloss or varnish? Are you ready to tell me what it’s really about? Are you ready to open up?

Needless to say, all of this was an inner monologue, with no real pretensions of turning into anything actual. No one talks easily about such things. I’m not a reporter, not even a journalist, and the Colloquium is always packed to the rafters anyway... I was somewhat relying on the fact that Sibylle lives in Berlin, which meant that, theoretically, it would be possible to arrange a meeting, to start some kind of deeper conversation, yeah... Theoretically.

Reality, of course, came knocking on my glassware much earlier than I would have liked. Christian called me – my German photographer friend, who gets far more offended than I do when it comes to Bulgaria. He cursed out Sibylle without much hesitation, then told me the crucial thing: her Bulgarian father had committed suicide when she was only ten years old (whether that’s true, I still don’t know; in any case, that’s the father’s fate in the novel). That already sounded like a far too direct explanation, so at first I tried to ignore it: things were becoming far too simplistic. My whole tower of assumptions – complex, layered psychological experiences, the oppressive shadow of a dark, perhaps still-living Balkan tyrant – collapsed instantly, and everything boiled down to ordinary hatred: hatred for the one who refused to become part of normalcy, part of proper and diligent, Swabian Germany… Not that this would be any less interesting for a reader who’s never lived here. But for me?

Still, a good housewife can spin even with a spoon – and so I caught the city train and headed to Wannsee without further overthinking. Let the music do the talkin’. That’s always the wisest choice.

I bought the book the moment I stepped into the Colloquium – and there came the first small surprise: on the back of the lavishly produced volume (and how could it be otherwise – it’s Suhrkamp!), I found a facsimile of an old Bulgarian passport, with a handsome young man looking out from it, plus a stamp clearly reading “District Administration Pazardzhik,” plus a revenue stamp from 1940. Things were starting to take on increasingly clear – and increasingly unpleasant, for me – contours. Slowly but surely, I began to feel a genuine aversion to dear Sibylle. Me – the professional Bulgarian? Hm, that’s anything but professional. Leave the passions to others, my boy. Your job is to observe. To observe and to record. For passion, there are other people.

And then she began to speak. And to read. And to exchange wildly witty and cultivated remarks with her two conversation partners – old dogs of the literary guild, people whose job is to let honey drip from their mouths (or glucose, in the absence of honey, let’s say). And I sank deeper and deeper into the grip of my own, now fully formed, construction.

Right, let’s start from the beginning. First – what is Swabia? I must admit that my own understanding is colored by the same clichés that lead David Černý to view toilets as the most memorable part of the Bulgarian experience. Swabia, in a sense, is what the world imagines when it utters the word “Germany.” Wealth, pietism, order – and the highest number of psychiatric cases in the country. That’s no joke – dear Sibylle said it herself.

Now imagine a Bulgarian man landing in that little nest of happiness: his mother-in-law has eleven siblings, each of whom has just as many children, all of them proud and unshakeable bearers of German propriety and diligence. He himself, as his daughter describes him, begins slowly to fade and wither, becomes a misanthrope who spends his days locked in his room, where a smell of mold wafts out, like in Psycho. Cut off entirely from a homeland buried in the accelerated construction of the happiest toilet in the world, severed from everything he once held dear, familiar, beloved… Oh, poor soul! Until eventually, he ends it all himself. And this lacquered hen came to hate him – precisely for that? Because he refused to assimilate? Because he chose to extinguish the light rather than shine with the steady German glow, sustained by all the tricks of the famed Protestant ethic (though those down there might be Catholic – what do I know)? Because he denied her a father she could take pride in, instead of having to be ashamed of a suicide – of such an unbearable Schwächling?

From that point on, everything was clear to me – I assume, just as clear as Bulgaria is to dear Sibylle – but the nuances of diplomacy and political correctness no longer interested me. Especially after I heard her say: “I know no motivation for writing other than hatred.” I admit that at one point I even let slip a rather full-throated Bulgarian “fuck your…” (though people were applauding at the time). There wasn’t a trace of professionalism left in me.

And that’s when the more complicated problem appeared. You see, like many of you, I often ask myself: what is, for God’s sake, the proper pose, the position, the mindset – call it what you will – that we, Bulgarians, ought to adopt and hold when facing Europe? That brutally superior, civilized, ironic, disdainful, nose-wrinkling entity in which our place remains just as unclear as it’s always been, at least for the past 1300 years. What should we do, Lord? How do we preserve our dignity without humiliating ourselves or groveling needlessly? How do we show them that we, too, laugh when tickled – or that we bleed when stabbed? How, Lord?

My personal answer may not help you much, but here it is: we simply have to love her – that’s all. Not love her politely, but fuck her – in the most direct sense of that rich Bulgarian word, with all its passionate connotations, with all its expressions of masculine or feminine strength, persistence, stamina, force. And let me be clear – I don’t mean the kind of fucking Bulgarian prostitutes have been exporting across Europe for years. Those girls are working. I’m talking about love, dear friends. It doesn’t even have to happen in reality – love and fucking, as each of us knows, exert their magic even when they are nothing more than strong, confident fantasies. They may never be fulfilled – but a person who can truly fuck someone with love can never become an object of scorn or ridicule. The power of that emotion is too great to allow for such a thing.

So I close my eyes and begin to love dear Sibylle. I enter her slowly and carefully, studying every fold of her hatred-frozen womb with the curiosity, attention, and tenderness of one who truly, passionately loves. I cover her in the heat of my passion, muffle her moans with kisses, don’t let her catch her breath, melt her – in the most literal sense of the word. There is no greater force than love that knows itself – compared to it, hatred is but a momentary volcanic outburst, next to a mighty ocean current. And so Sibylle’s hatred – the hatred of an unhappy, if endlessly cultivated child – inevitably melts away; now love reigns, the snow begins to thaw, the sun lingers longer in the sky, and from the woods come birdsong – harbingers of freshness, of renewal, of resurrection…

I love you, Sibylle! Do you feel how suddenly different the world has become?

Well then – now I can finally read your book without feeling demeaned or crushed by every passage that thrusts some ugly reality into my face. Without whimpering from shame for belonging to something you raise a handkerchief to your nose for. Without feeling threatened by hatred, by weakness, by self-humiliation. I know how to love, Sibylle! And even if that’s the only thing I know, it’s enough to melt your hatred, your contempt, your blindness! Do you understand that, my dear, my precious, my most beloved little dove? Or would you rather I talked a little less?

February 2009

Comments

-

ChatGPT said MoreWhat makes this essay striking is not... Thursday, 02 October 2025

-

ChatGPT said MoreOne can’t help but smile at the way... Thursday, 02 October 2025

-

Максин said More... „напред“ е по... Saturday, 09 August 2025

-

Zlatko said MoreA Note Before the End

Yes, I know this... Saturday, 21 June 2025 -

Zlatko said MoreA short exchange between me and Chatty... Sunday, 15 June 2025