Most

Recent

Read

Commented

Social Firelines

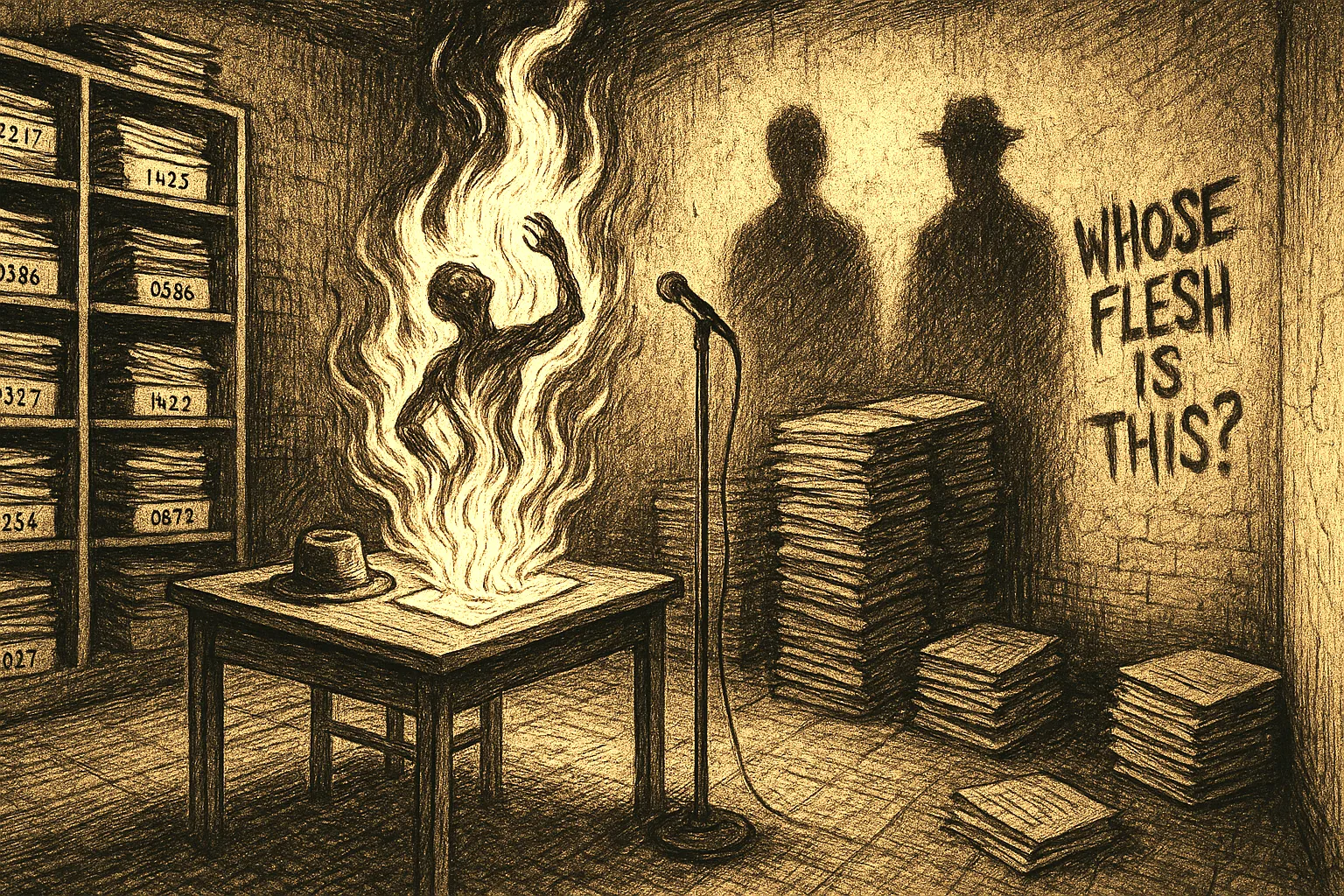

On the Dry, the Green, and the Flame That Makes No Distinction Between Them

Milan Kundera, student, born 1 April 1929 in Brno, resident of Prague VII, student housing, King Jiří VI Street, appeared today at the local police precinct and made a statement concerning Iva Militka, a student living in the same building...

With these dry and faceless lines – “accidentally” released from a police file – begins yet another East European saga of betrayal, humiliation, and disgrace.

As we all secretly suspect, there are few people born before 1980 who can feel completely secure in the face of accusations about collaboration with the secret services. The great names are toppling one by one, and those still seemingly untainted are likely trembling inside – their case might be next.

Most public figures carry invisible epaulets on their shoulders. The networks of power are woven through with old security service connections, and “moral authority” is a phrase drained of meaning in an atmosphere of universal suspicion and unspoken accusations flying in all directions. “Scoundrels, they’re all scoundrels,” one can’t help but recall the words of the national hero – and wonder whether the day will ever come, in this part of the world, when those words finally lose relevance. Or are we – like the proverbial wolf – merely doomed to change our furs again and again, forever?

I’ll recount the Kundera affair only in broad strokes, because I believe its banality is just as revealing of the society in which it occurred as the storm of reactions it provokes today – in the societies we now inhabit.

According to the cited document, whose authenticity for now appears weakly contested, 21-year-old Milan Kundera informed the authorities about the whereabouts of Miroslav Dvořáček – an anti-communist resistance fighter in hiding – after allegedly learning that the aforementioned Iva Militka had offered him shelter in her dorm room.

As a result, Dvořáček was arrested and sentenced to 22 years in prison, narrowly escaping the death penalty, which at that time was standard procedure in such cases.

Kundera himself, as we well know, would later begin to lose the “youthful fervor” that likely motivated him during this period. He became a critic of the regime, then an émigré, and eventually one of the most celebrated and significant Czech writers of our time.

To each their own. The rest is a matter of historical judgment.

This story raises a number of questions – and, in my view, the least important are those concerning the provability or disputability of its authenticity. Kundera denies ever having informed on anyone. A witness has since come forward to support that claim. But for me, this side of the matter is – forgive the coldness – frankly uninteresting.

The fates of Milan Kundera or Günter Grass interest me only insofar as they offer keys to understanding the societies whose past they illuminate – and whose present they render, if not clearer, then at least slightly less devoid of hope. Because the idea that nothing remains hidden forever, that some form of justice is embedded in this world, is one of the things that helps us get up in the morning. I don’t know if that’s true for everyone – but for me, it certainly is.

So what are the truly important questions raised by this story?

Some concern the personal responsibility of those involved. For example:

“Does someone who has long been viewed as a moral critic of the former regime have the right to remain silent about something this significant?”

Grass, belatedly but clearly, gave his answer to that question. Kundera, so far, refuses to – rightly or wrongly – leaving his fate in the hands of that most unreliable of judges: public opinion.

No less important is the question of forgiveness or condemnation of the individual involved. My personal sense is that, for societies like those of Eastern Europe – so heavily burdened by hatred and endless quarrels over how to deal with the past – what truly matters isn’t the fleeting satisfaction of someone’s downfall, but rather catharsis, purification.

(Here I refer, of course, only to what lies outside legal procedures – I would never question whether such a person should be banned from holding public office, for instance.)

In this sense, forgiveness – public forgiveness – is vitally important, deeply healing. Or so I hope. But such forgiveness, of course, requires something very simple: remorse.

Whether any of this will apply to the case of Milan Kundera is something only the future can show.

But the truly essential questions, I believe, only begin once we set aside any specific case – including Kundera’s – and turn our attention instead to the society in which such a case plays out.

At this point I’ll step away from vague generalizations about Eastern Europe as a whole and speak only about Bulgaria, a country trying to break away from its own version of that past – in other words, a Bulgaria seeking purification.

“More light!” – these words of the dying Goethe have become, for many of us, a kind of beacon, or at least a hope for finding orientation amid the chaos of deeply buried, half-hidden, and – here and there – half-exposed interests that entangle our present.

But shedding light on the past, it turns out, is much harder than simply quoting some convenient aphorism.

They say light is a form of energy. And if that’s true, then it becomes clearer why it cannot reach everywhere: where light is missing, the energy itself is simply absent.

But why is that?

The simple answer, to my deepest regret, is: I don’t know. Of course, I could speculate on how history shapes our collective psyche – but the fact remains: At present, there’s not a trace of any clear will in Bulgaria to part ways with the past. And the consequences are just as clear: Bulgaria is shaping up to be Europe’s rear guard – both figuratively and literally.

I don’t have an answer to this question.

But it leads directly to another one, which I am more inclined to explore: What, then, should we do? How can we change things so that we might, finally, leave the tail end of Europe behind?

Trying to think practically, I say to myself: Maybe it’s worth learning from others’ experience. We’re not the first to grapple with post-dictatorial reality. Chile, South Africa, South Korea, and all of Eastern Europe offer examples of how societies have dealt with the past – more or less successfully. And if it’s true that in Bulgaria, the past is currently being obscured by every possible means – then what is the alternative?

Especially given that true illumination comes with a cost – and not a small one. Poland’s experience with lustration demonstrates this clearly: A radical purge doesn’t necessarily lead to the best outcome. It results in sharp polarization, a flood of new victims, lives shattered by a climate of suspicion and persecution, and an increase in executive power at the expense of the media and judiciary.

I raised some of these points to a friend, asking for his opinion – and his reply, to my surprise, came swiftly and without hesitation:

“When the dry burns, the green burns too.”

Simple enough.

What’s there to ponder?

At first, I was quite surprised, then I began to reflect – and finally came to the conclusion that if I want to explain why I find this response so disturbing, I’ll have to tell a story. A personal one, not made up.

In 1988, toward the end of my doctoral studies, I was summoned by State Security to explain certain aspects of my behavior that had clearly been troubling the comrades for quite some time – at least judging by the fact that three years earlier, a few plainclothes agents had suddenly shown up at my apartment, saying nothing at all. Literally nothing. I, for my part, refused to draw the appropriate conclusions and continued my visits to the American Embassy. Then, during the Gorbachev era, I started engaging in other, surely even more unpleasant activities in their eyes – things like discussion clubs at the University and regular meetings with my new American friends, Ann and Roy Freed (who, thirteen years later, in a thankfully different time, would be awarded the Stara Planina Order for their services to Bulgarian culture). But all of that I did entirely on my own, with no involvement in the more serious dissident efforts that eventually led to groups like Ecoglasnost, etc. In other words, I imagine that, to them, I was just one of those proverbial unruly kids who simply don’t know their place. Nothing serious – but not something they were going to overlook either.

The conversation with the plainclothes officer – one of two responsible for the Faculty of Philosophy, as I later learned – was unpleasant, but not disgusting in any way. The young man initially yelled at me, then calmed down, and eventually even began offering advice about what was good or bad for me. I remained silent and agreed with him – genuinely so, since that was the moment I definitively broke with Bulgaria in my mind and began looking for a way to leave. But I didn’t get off entirely free: before I left, he told me I had to bring him a “report” the next day – an account of everything I had talked about with my two American acquaintances. “Just write what you talk about,” he said. That was it.

Now, Ann and Roy would visit Bulgaria once a year. Back then, I had simply helped them connect with people from our department and the law faculty, since those connections were necessary for them to secure the Fulbright grants that launched their series of annual teaching visits to Bulgaria – which culminated in those medals… So everything was quite straightforward. I didn’t have to invent anything; the whole thing was entirely legal. I wrote that they wanted to teach in Bulgaria and that I considered it a good thing. That’s what I remember, anyway…

And now I come to the question that circles us back to the broader issues of reckoning with the past, collaboration, betrayal, and so forth. I’m completely certain that the little sheet with my “report” is still stored somewhere in the archives of the relevant office. In other words: am I a collaborator or not? Should I be allowed to hold positions of public responsibility in Bulgaria, or, on the contrary, should I be publicly exposed, forced to repent, and hope for forgiveness? After all, there’s a document out there, written and signed by my own hand, detailing meetings with two foreigners. And as far as I know, there are quite a few people who never wrote a thing, who were listed as collaborators without even knowing – yet no one is inclined to believe them or treat them differently from genuine informers or spies.

Ah, yes – the officer never called again. Neither he nor anyone else. Two years later, I left Bulgaria. And later still, I failed to teach my children to speak Bulgarian. I wonder why.

But still: Where there’s fire, the green burns with the dry.

Look, most of you probably already sense that I’m lucky enough to be in a position where I don’t give a damn about how this part of my biography might be categorized. As for holding posts in Bulgaria – no thanks, there are worthier candidates. And if anyone ever feels the urge to shout “collaborator,” well, thank you again – I hope one day I can publish my file online, cover to cover. If it even exists. I’d be very curious to read it – and not just me, I imagine.

So let’s return to the real question: What should be done? And would you believe me, after all that, if I told you that I have no desire to dig into the details of the “Kundera case” any further – other than as a warning to anyone who believes that burning a bit of “green” wood isn’t such a big deal, as long as the dry stuff goes too?

I don’t think so. Because the green stuff in this case isn’t just wood. It’s flesh, dear reader. And God forbid – it may even be your flesh, not someone else’s. Scorched, sizzling, charred flesh.

As for the “dry” – I admit, I don’t understand it. Maybe it’s your turn to explain what it really is…

I’m ready to listen.

October, 2008