Most

Recent

Read

Commented

Bulgarian Self-Image

On responsibilty

I’m starting yet another short essay with a familiar mix of feelings: some pleasure, and – inevitably – some tension. The pleasure comes from the discussions that sometimes arise here. However incomplete or misshapen they may be, they remain one of the few genuine rewards for all the effort behind this magazine.

The tension comes from experience: these discussions rarely unfold with mutual understanding, or even the minimum of mutual respect.

But enough. The work matters more than the feelings – even when it sometimes feels like tilting at windmills, as it often does for people like us, up here on Europe’s periphery.

So: on to the text, which is nothing more than a commentary on a much larger and vastly more important piece by Noam Chomsky, The Responsibility of Intellectuals, Redux.

The responsibility of intellectuals. Responsibility, period.

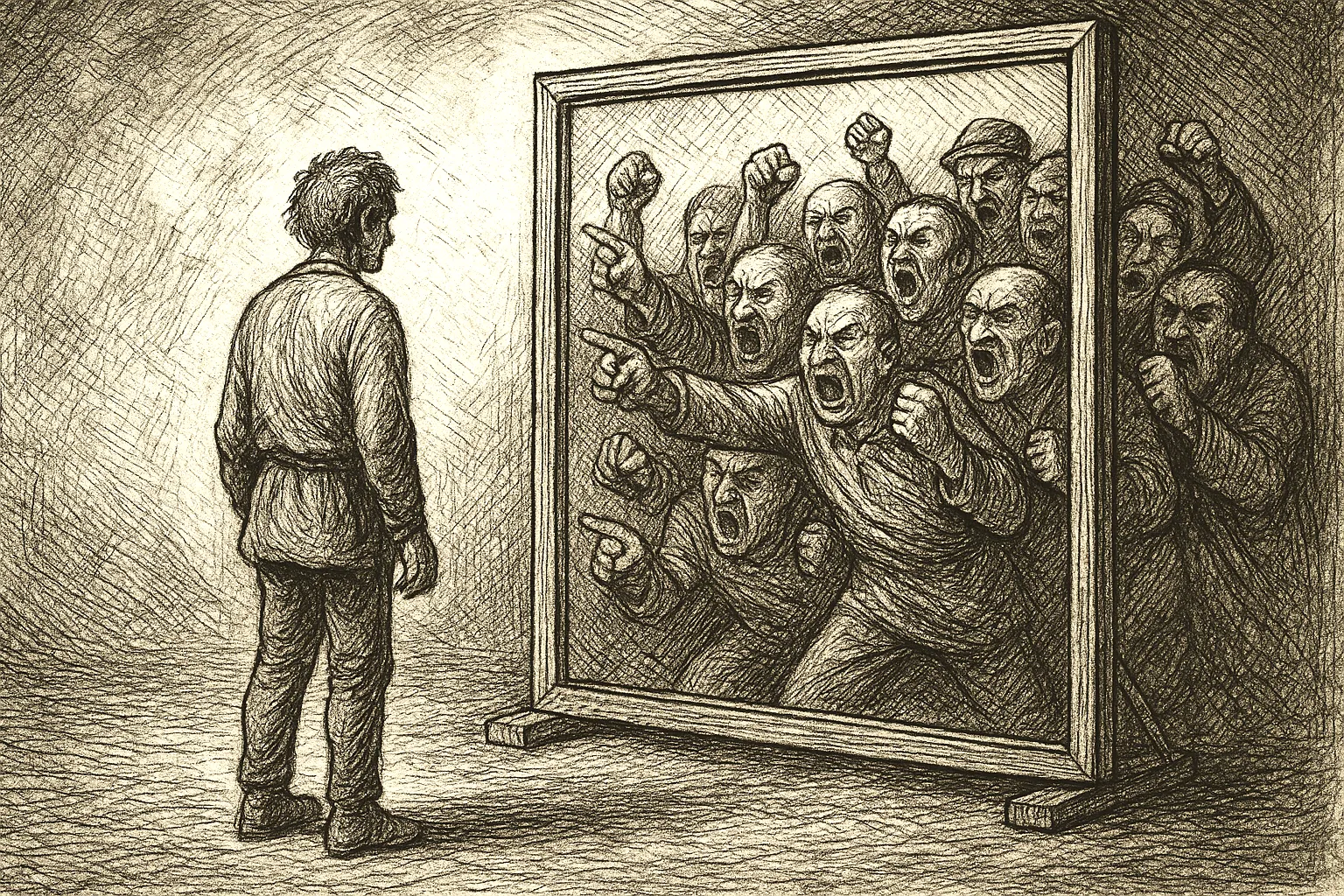

It’s a difficult, unpleasant subject – maybe because it always drags us into confrontation with ourselves, with our own conscience. And that, in turn, becomes a confrontation between some kind of “us” and some kind of “them” – because facing ourselves directly is simply too painful.

So what does the wise man from Boston tell us?

Nothing new, really: that the real responsibility of intellectuals is to direct the public gaze – not outward, not at someone else’s plate (as one old Bulgarian proverb puts it), but inward, at ourselves. At our own responsibility. At our own complicity in shaping the world we live in.

And here, right from the start, I run into the same wall I always hit in conversations with my fellow countrymen.

Every attempt I’ve made to redirect this blurred Bulgarian “public gaze” inward – instead of outward, toward the usual culprits for our miserable state (listed chronologically: Byzantines, Turks, fascists, communists, Russians, and more recently anyone who deviates in any way from the drab average of Bulgarian existence – foreigners, homosexuals, ethnic minorities, or – best of all! – the powerful and the prosperous: fuck them! Because as we all know, it’s crooks all the way up, brother, and no one else could possibly be to blame!)…

All these attempts have been flatly, stubbornly, and silently rejected. Dismissed. Pushed aside. Condemned at the invisible gatherings of fellow sufferers. Bulgarians. Us. Ourselves.

I’ve made more than a few attempts to start a conversation about our own responsibility for our recent history. Not the responsibility of the communists – that’s too easy. I mean our own: the responsibility of those who stayed silent, who rubbed their hands quietly in approval. The ones who helped divide the nation into two opposing camps – or more precisely, into many camps, multiplying daily in our perfectly Balkan version of Hobbes’s war of all against all – minus the Leviathan.

Today, in the latest round of finger-pointing – and in what may be the least productive direction of all (“Off to the gypsy camp with them!”) – I’m trying, more cautiously now, to suggest that once again we’re aiming at the wrong people.

You can’t saw off the branch you’re sitting on.

(And for the record – I’m not the one who said “The Roma are our future.” That was the well-known Bulgarian sociologist Haralan Alexandrov – someone who understands the Bulgarian situation far better than I do.)

Still, the point stands: You can’t blame the branch for being there after you’ve started sawing at it. It just doesn’t work.

Let’s pause on something.

Imagine that, a hundred years ago, someone had dared to say openly that the Jews – seen, perhaps, as an emerging elite – would one day become representative of the future of a great nation. That they would build strong, unshakable institutions and fiercely defend their collective interests.

The reaction would likely have been just as hostile as it is today when someone like Haralan Alexandrov says that the Roma are our future.

Now, I’m not blind to the obvious differences between Jews and Roma – God forbid I collapse into slogans.

But if you look into the history books, you’ll see that back then, Jewish culture – its intellectual and practical power – was more or less invisible to the broader society. Just like Roma culture is today. That’s what it looks like, if you bother to look closely.

And I, personally, know a few Roma who are both brilliant and effective – intellectually and practically.

One of them, with two PhDs from American universities, is now teaching here in Berlin, at the Free University – one of Germany’s most prestigious academic institutions. Yes, I know him. And I’ll be meeting with him soon.

But let’s return to the question of responsibility – and how differently we apply it to others versus ourselves.

Not long ago, in one of our stunted discussions here, I cautiously raised the question of how we judge the responsibility of our Serbian brothers for their own recent history.

(I didn’t even bring up the Macedonians or Albanians – that would’ve instantly blown things out of proportion.)

I got no reply.

Still, I won’t shy away from offering another “counterproductive generalisation”: when it comes to Serbia’s guilt, we tend to agree – they’re to blame. Of course they are. Who told them to be so eager to… and so on. You know the tune.

But I won’t sing that song. I’ve made a habit of staying out of it. Because, as I’ve already said, my concern is our own plate. When it comes to someone else’s, I leave the talking to louder voices.

But what happens when we turn the same question toward ourselves – toward our own fate, our own responsibility? Suddenly, the lens flips. Everything snaps back into its “proper” Bulgarian place. Who’s responsible for the deep divide between us and the country’s minorities?

Not us, of course! The communists are.

We love minorities – don’t we? We’d never let anyone say a bad word about them, heaven forbid!

And now that we’ve run out of communists to blame, the target shifts – naturally – to the ruling elite. They corrupted the minorities. Bought them off with cash and promises, just for their miserable little votes. Whatever happens in this country, it always ends the same way: two camps. “Us” – the good, responsible people. (But not for that, of course. For something else.) And “them” – the guilty ones of the week. The bad ones. The others. The not-us. The ones who spoil the landscape. The ugly ones. Barefoot, toothless, mouths stinking from afar. We gleefully paint them across social media as drooling, degraded, barely-human figures – examples, warnings.

“This is what happens,” we say, “if you don’t keep your distance.” Because the difference between them and us is… what, exactly?

“Scratch the Russian,” Dostoevsky once said, “and you’ll find the Tatar underneath.” And when you scratch the Bulgarian – what do you find?

Can anyone tell me?

And is it really a coincidence that every time a foreign photographer turns their lens on our minorities – who, by some foreign logic, seem more interesting than “us” – we leap up in outrage?

“Is that all you found in Bulgaria? That’s not us! Those are the others. The ugly ones. The wild ones. The different ones. We are something entirely different…”

But if we really are something entirely different – Why does it hurt so much?

Responsibility, dear compatriots, is heavier here than the proverbial hot potato. It’s something no one wants to carry, and few are even willing to touch. Probably because taking responsibility always means starting from the only place that actually exists in this world we share: oneself. It means confronting your own “I,” your own “we,” your own share of guilt. It means repentance. And from there, it means the hardest step of all – trying to change, to begin something new. Something still unfamiliar in this country. Something that turns the gaze inward, not outward. Not toward the eternal Bulgarian scapegoat – the other – but toward ourselves.

Yes, judging by the American’s words, the situation over there isn’t so different. It probably never has been, anywhere. Just today I got one of those familiar comments:

“So what, are we the only nationalists? Look at them! And them! And the others!”

And with that, I couldn’t help remembering Todor Kolev’s old song:

“How will we ever catch up with the Americans?”

How, indeed – if out of everything we see in their world, we always choose to imitate only the things we’ve already been doing forever, long before they even showed up?

How?

Tell me.