Most

Recent

Read

Commented

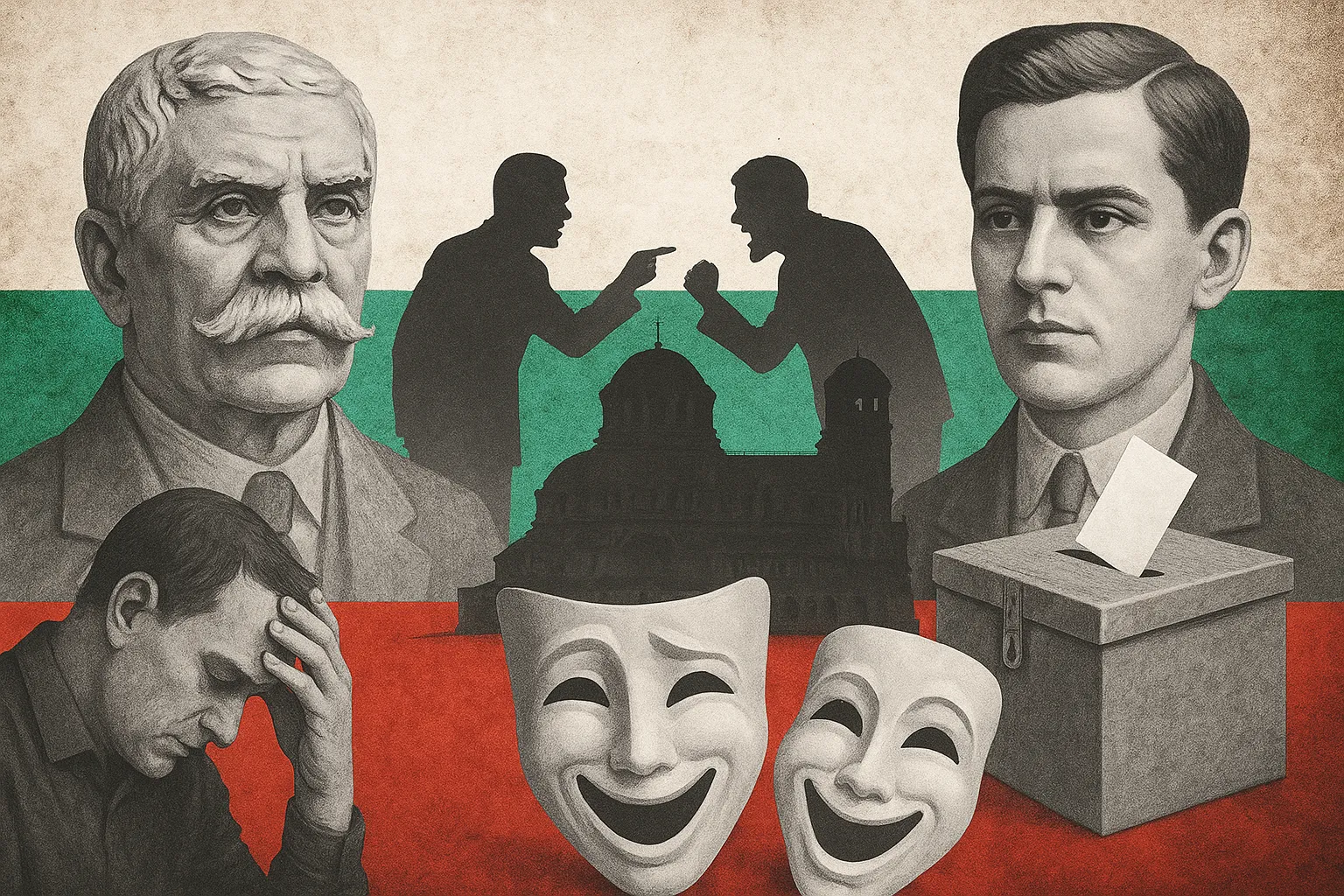

Bulgarian Self-Image

The Two Faces of the Bulgarian Soul: Correctness and Confrontation

In the personalities of the two great contemporary Bulgarian literary figures, one can glimpse more than individual temperaments. They embody two enduring archetypes of human – and specifically Bulgarian – behavior: on one side, the pursuit of absolute correctness, the anxious wish to avoid controversy and secure legitimacy by impeccable conduct; on the other, the nearly obsessive search for confrontation über alles, as if conflict itself were the only reliable proof of life. These are not just psychological quirks or literary postures. They are social blueprints, revealing the deep, unhealed fractures in Bulgarian cultural identity – fractures that persist beneath the surface of modernity, bureaucracy, and imported liberalism.

Two archetypes – one wound

Let us begin by stripping these types to their essence. The “correct” personality is the child of insecurity. He believes that safety lies in composure, moderation, and neutrality – in saying nothing too sharp, doing nothing too risky, being always “proper.” This drive toward correctness is not necessarily cowardice; it often springs from an intelligent reading of one’s surroundings. In a culture where deviation has long been punished – whether by the whip, the party, or the mob – correctness is a rational adaptation.

The “confrontational” type, by contrast, is born from the same fear but reacts inversely. He feels suffocated by the polite silence of his peers and therefore seeks liberation through rupture. His logic is: if harmony leads to decay, let there be war. He breaks decorum the way others break bread – with religious fervor. To confront, to offend, to scandalize becomes not only a method but a moral code.

The two appear to be opposites, yet they share a common root: both are responses to the same cultural trauma – the trauma of smallness, of dependence, of being perpetually under someone else’s shadow. In one case, the reaction is mimicry; in the other, revolt. The “correct” writer bows before imagined standards of respectability, often imported from the West; the “rebellious” writer spits at those standards and wraps himself in the flag of authenticity. Both are trapped in a dialogue with an invisible Other who must either accept or reject them.

The cultural background: Bulgaria as a low-trust society

To understand why these archetypes remain so dominant, we must look beyond individual psychology to the social climate that sustains them. Bulgaria, like many post-Ottoman, post-Communist societies, is a low-trust culture – meaning that horizontal bonds (between citizens, colleagues, peers) are weak, while vertical ones (to authority, patronage, hierarchy) are strong.

In such societies, success depends less on collaboration than on navigating power safely. The result is a pervasive social anxiety: everyone seeks legitimacy from above while suspecting betrayal from below. The “correct” intellectual becomes the perfect servant of this environment – he is cautious, deferential and allergic to open conflict. The “confrontational” one, meanwhile, mirrors the same anxiety but translates it into aggression: if no one can be trusted, I will trust no one; I will speak against everyone.

The cultural ecosystem of modern Bulgaria reflects this duality vividly. On one end stand the “respectable” writers, curators, and academics who measure every word, polish every phrase, and keep ideological distance from anything “divisive.” They speak the language of moderation, European values, and “balanced perspectives.” Their work often possesses craft but little urgency; it is art as compliance.

On the other end are the perpetual rebels – the self-exiled critics, the angry columnists, the rejected geniuses who see every institution as corrupt and every compromise as betrayal. They are the romantic heirs of Botev’s curse and Geo Milev’s martyrdom, convinced that suffering is the only badge of authenticity.

The tragedy is that both camps are sincere. The first truly believes that civility protects culture; the second – that truth must wound to heal. But their battle takes place within a vacuum – a society that neither rewards excellence nor tolerates real dissent. Thus, correctness and confrontation become two sides of the same impotence.

The psychological root: shame and fear of exposure

At the heart of this polarity lies a single psychological constant: shame.

Bulgaria is a shame-based culture, not a guilt-based one. Guilt is internal – it presupposes an inner moral compass that can judge one’s own actions. Shame, by contrast, is external – it depends on how one appears in the eyes of others.

The “correct” figure fears being shamed for error or excess; therefore, he cultivates blandness as a shield. The “confrontational” figure fears being invisible; therefore, he courts scandal to ensure recognition. Both operate under the same emotional economy: my worth depends on how I am seen.

This dynamic explains the Bulgarian obsession with reputation, with “what people will say.” It also explains the peculiar cruelty of Bulgarian public life – the glee with which society punishes those who fail or deviate. Because everyone lives under the tyranny of external judgment, every downfall is a communal holiday.

The intellectual, in this context, becomes either an anxious diplomat or a doomed martyr. There is almost no middle ground for those who simply wish to do their work honestly, without either pandering or posing. They are the invisible majority – the quiet, decent, unheroic Bulgarians who sustain the culture from beneath, uncelebrated and unprotected.

The political dimension: mimicry vs. rebellion

These archetypes mirror Bulgaria’s political trajectory since 1989.

The “correct” mentality corresponds to mimicry – the strategy of adopting Western democratic vocabulary, formal institutions, and rhetorical manners while avoiding real structural change. This mimicry is not malicious; it is a survival strategy. After decades of isolation, Bulgaria sought entry into the European family by demonstrating “good behavior.” The result: an endless theatre of reforms without transformation, gestures without consequences.

The “confrontational” mentality, meanwhile, corresponds to rebellion – the populist, nationalist, or cynically “authentic” reaction to the perceived hypocrisy of mimicry. It mocks the “Brussels dialect,” despises elites, and glorifies the “real people.” Yet it, too, is hollow, because its rebellion depends on the very system it rejects. It defines itself only by opposition, never by construction.

Together they form a perfect closed circuit:

- Mimicry breeds boredom and alienation →

- Rebellion erupts as catharsis →

- The chaos justifies new mimicry in the name of “stability.”

The cycle repeats. No synthesis, no growth – just a pendulum between the two ghosts of the Bulgarian psyche.

The cultural pathology of smallness

Underneath this entire dynamic lies what might be called the pathology of smallness – the internalized belief that we are too small to matter, too peripheral to change anything, too late to join the modern world on equal terms.

The “correct” intellectual tries to escape smallness by conforming to universal standards – to write like a European, think like a Westerner, behave like a civilized cosmopolitan. The “confrontational” one tries to subvert smallness by turning it into pride – we are the misunderstood, the pure, the tragic exceptions.

Both are strategies of denial. Neither asks the more difficult question: what does it mean to be small and still whole? To accept one’s scale without shame or heroics, and to work precisely within it.

This failure of scale is why Bulgarian culture swings between grandiloquent gestures and provincial inferiority. Every attempt at universality feels borrowed; every attempt at authenticity feels parochial. We have not yet found a way to be provincial with dignity – to accept the local as a vantage point rather than a prison.

Historical echoes: from submission to rebellion and back

History explains much of this. For five centuries, survival meant obedience. The Ottoman system rewarded quiet adaptation; those who resisted were erased. After liberation, that inherited servility transmuted into a desperate hunger for recognition. We wanted to prove ourselves “European” – to shed the stigma of the East.

Then came Communism, which once again equated survival with compliance. The cost was the destruction of trust: one could not be sure who was listening, who might report. Speech became dangerous, so people learned to speak indirectly, to hide opinions under layers of irony or silence. When democracy arrived, this collective trauma did not vanish; it merely changed shape.

Thus, the current split between correctness and confrontation is not new – it is simply the modern mask of an old civilizational rhythm: submission, eruption, exhaustion. A people oscillating forever between obedience and insurrection, never at home in stability.

The hidden national reality beneath the surface

Beneath all the noise, Bulgaria’s cultural problem is neither aesthetic nor political but existential. The country has not yet resolved its relationship with freedom.

Freedom, properly understood, is not rebellion, nor is it conformity. It is the capacity to stand alone without seeking constant confirmation – either from the West or from one’s own resentments. In that sense, both archetypes are evasions of freedom:

- The correct one escapes freedom by hiding behind rules.

- The confrontational one escapes freedom by declaring war on everything that limits him.

Both depend on an external frame – the first on approval, the second on opposition. True freedom would mean inner sovereignty: the right to act without either permission or applause.

Such sovereignty is still rare in Bulgarian culture. Our institutions neither protect it nor reward it. Writers who attempt it usually vanish into obscurity, while the public oscillates between worship and ridicule. This absence of mature autonomy – the inability to inhabit complexity without turning it into hysteria – is perhaps the most Bulgarian trait of all.

What the two figures reveal about us

If we return to the two literary figures that inspired this reflection, we see how profoundly they mirror the society that produced them. The one who seeks correctness does so because he has intuited that in Bulgaria, exposure kills. The one who seeks confrontation does so because he has understood that in Bulgaria, silence kills faster. Each is right within his own logic. Each carries a fragment of truth that the culture, as a whole, refuses to integrate.

In a healthier ecosystem, these two energies would complement each other – rigor and risk, restraint and passion. But in our fractured context, they annihilate each other instead. The cautious neutralizes the brave; the brave discredits the cautious. The result is a sterile stalemate: literature as etiquette, criticism as vendetta, public debate as theatre.

Toward a third stance: irony and responsibility

Is there a way out? Possibly. It begins with irony – not the cheap cynicism of Facebook commentators, but the mature irony that allows one to see both sides without collapsing into either. Irony is the art of distance, and distance is what Bulgaria chronically lacks. Everything here is personal, tribal, final. The moment we learn to laugh at ourselves without hatred, the paralysis might begin to thaw.

The second step is responsibility – the willingness to speak truth without theatrics, to disagree without excommunication, to build without worship. Responsibility is the adult form of both correctness and rebellion; it integrates discipline with honesty.

It is precisely what is missing from our public life: not more rage, not more politeness, but more adulthood.

Coda: between fear and maturity

The story of these two archetypes is ultimately the story of a culture still haunted by fear – fear of being punished, ignored, misunderstood, or ridiculed. Every Bulgarian generation has reinvented this fear in its own key: the poet silenced by censorship, the journalist mocked by trolls, the thinker dismissed as “pretentious.” Fear breeds compliance; rebellion breeds more fear.

But history is not destiny. A mature society learns to live with its contradictions instead of dramatizing them. Bulgaria will begin to change the moment we stop treating disagreement as treason and politeness as cowardice – the moment we understand that civilization is not a mask but a habit, and that confrontation can serve truth only when it is rooted in respect, not resentment.

Until then, our cultural life will remain a mirror of these two wounded archetypes:

the Correct One, who fears to err, and the Confrontational One, who fears to vanish.

Both are still playing the same ancient game – a duel between the terror of exposure and the longing to be seen.