Most

Recent

Read

Commented

Family Dynamics

The Tears

„Shall I leave you alone?“ his mother asked from behind, and coughed – sharp, cutting.

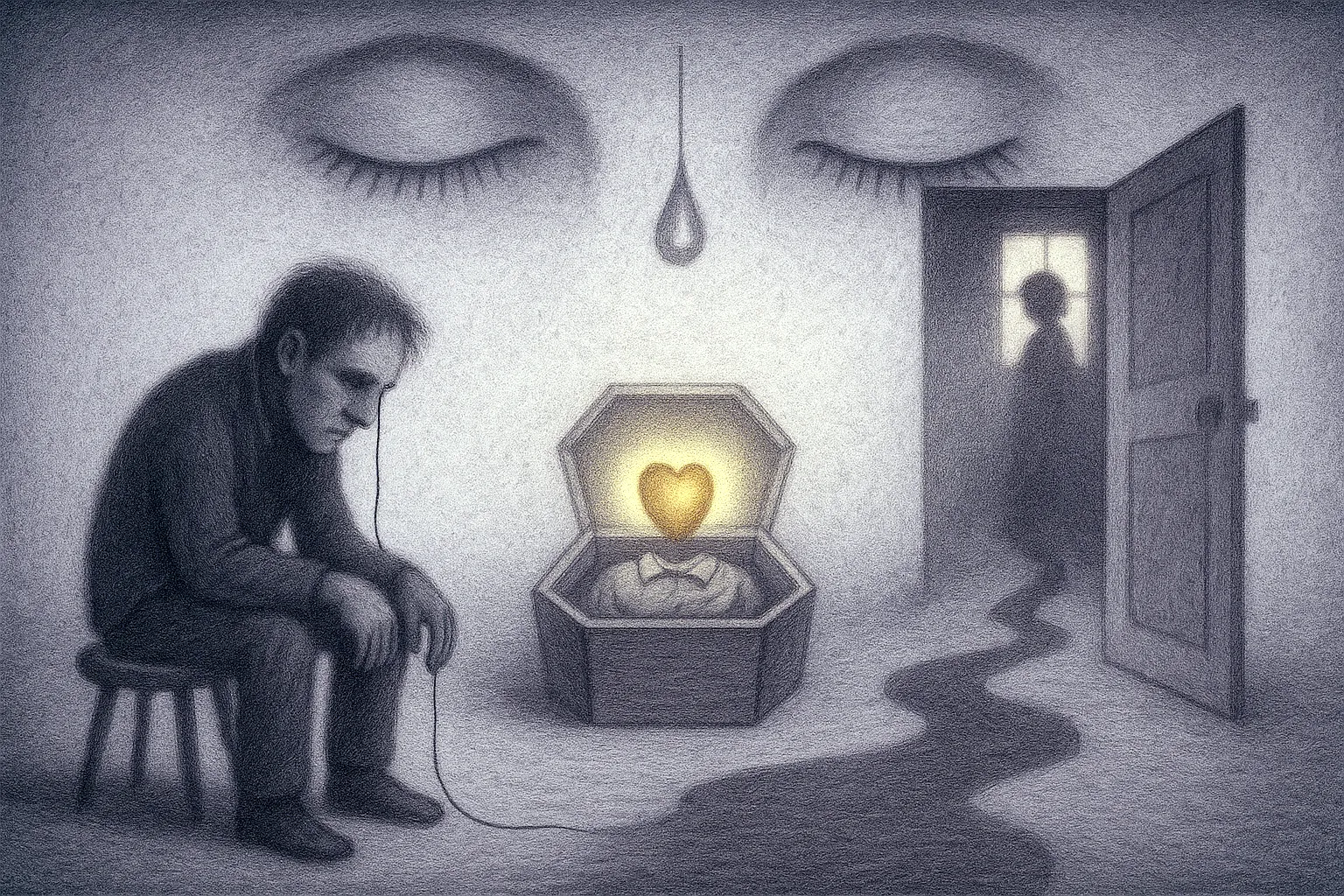

He didn’t answer, pulled one of the stools toward him and sank heavily onto it. The coffin swayed threateningly, and he propped it with his knee, glancing in alarm at the dead man, who had nearly toppled onto the floor. It was a cheap, flimsy coffin, made of thin slats and far too shallow for the still-heavy body of his father, which stuck out by at least a hand’s length above the side walls. „Tomorrow we’ll have to tie the lid with rope if we don’t want to lose him on the way,“ he thought, then wondered if it wasn’t proper to kiss his father – but the waxen coldness repelled him, and he settled for adjusting the small bunch of artificial flowers tucked into the lapel of the old, worn jacket.

His mother closed the door behind her. He buried his head in his hands and drifted off.

***

The phone rang just before midnight and his heart jumped. He hated those late calls – had always hated them. He knew it would come sooner or later, but had still hoped it would find him in the middle of the day.

It was Lucy, his brother’s wife. Her voice was trembling – he had to strain to understand her.

„When?“ he growled, pressing the receiver hard to his ear. The pain calmed him a little.

„Today, two hours ago. A heart attack, while going up the stairs. Died on the spot.“

„How’s Brother doing?“

„Crying, won’t speak. The funeral is the day after tomorrow. Can’t be postponed – there’s a power cut coming, and they can’t keep him in the morgue for more than two days.“

„Alright, I’ll manage,“ he said and cut the line. His ear ached and let out a thin, high whistle from deep inside.

„Shall I leave you alone?“ his wife asked from somewhere on the other side of the bed.

He growled something inarticulate and pulled the blanket over his head. Now it wasn’t just his ear hurting – the pain had spread into the tiny bones at the base of his skull and made him grind his teeth softly, so it wouldn’t be heard. He tried to find something in himself that he could call by some decent name – grief, sorrow, maybe even despair – but inside there was nothing. He felt hollow and light, so light that even a fart could launch him forward like a jet engine. Still, the dinner weighed in his stomach like the stones in the wolf’s belly – he tossed and turned in vain, trying to find a position in which he could fall asleep. From her breathing, he could tell she wasn’t sleeping either – that she wanted to say something to him, maybe something kind, good, human – but the emptiness had left him powerless and drained, like a fish on dry land, and now he couldn’t gather the strength to respond to her call – until finally she gave up and fell asleep, leaving him alone and listening to the muffled ticking of the wall clock, which today, who knows why, reminded him of Dante’s tercets.

***

Apparently he had dozed off in the end, because he didn’t remember the usual panic before landing – came to only when he felt some hand shaking him gently, but insistently. It was one of the stewardesses – not quite a young girl, but with a fine, tight arse, which he’d tried in vain to sneak glances at back when they left Berlin.

„We’ve arrived,“ she said with a professional smile. „Welcome to Sofia.“

„What time is it?“ he asked, horrified, while yanking his backpack from the overhead compartment. „Did we arrive late?“

„No, on the contrary,“ she looked at him, surprised, almost frightened – but he was already rushing down the empty corridor like some strange, distracted terrorist who’d forgotten to carry out his mission.

„What’s up, man? Looking for a taxi?“ The bearded, long-haired guy sized him up, puffing on his fag. „Come with me – we won’t haggle too much.“

He stayed silent.

„Hey, man, are you okay?“ the guy looked at him, concerned. „You’re pale as a sheet – are you feeling ill?“

„My father… they’re burying him tomorrow,“ he croaked, suppressing the pain that this time had settled in his stomach. „I need to catch the night train to Shumen, at eleven. Or you could drive me there – but I don’t know if I have enough money.“

The guy whistled and checked his watch.

„Twenty minutes from here to the central station… Alright, man, just pray all the Sofia traffic cops are drunk tonight. Let’s go.“

The streetlights along Tsarigradsko Shosse flickered past above their heads like fence posts.

The driver gripped the wheel with white-knuckled hands, softly humming Rufinka to himself, and only now and then slammed the horn with fury before muttering,

„Our angels are strong, man. We got lucky again.“

He was hunched in the seat, reminding himself that at least he’d fastened the seatbelt – closed his eyes with every overtake, and pressed the backpack against his stomach with both hands. Good thing he hadn’t eaten anything.

„Go, go, man – you’ve got three minutes! Don’t screw it up now, bro – run! Keep your money, just run, you hear me? You think I don’t have a father too?“

He promised himself he’d give the fare to the first Gypsy kid he saw, then dashed wildly across the filthy floor of the empty, stinking lobby.

The fat woman behind the murky window hastily counted his money, growled something at his back and went back to dozing. He took off again, the pain chasing along with him.

***

„I made it, Dad. I got here,“ he whispered tiredly.

The fat candle wedged between the dead man’s fingers flickered hurriedly in response.

„Ugh. I’ll take off my shoes. Sorry if I stink – been on the road since yesterday.“

The April morning, grey and smoky, wasn’t in a hurry to drive out the darkness outside. He carefully dragged the stool over to the wall, leaned back and gladly let the cold of the unheated wall seep into him. He shivered, pulled away. It wasn’t that hot. He sat for a while, stared at the flat frog-like, unfamiliar face, sighed.

„You stink too, Dad – I’ll open the window a little, just a crack. I know you don’t like draughts.“

The candle flame trembled angrily, but then settled, calmed. The old man had always been an understanding soul.

„A kid helped – one of ours. Almost killed us both – I thought we’d be going up together… Ugh, sorry, I’m rambling. Must be the lack of sleep.“

They sat a bit longer, quiet.

„Dad, I’ve got to ask you something – there’s no one else,“ he finally dared. „Hope you won’t be offended… I’m a little ashamed, but what can I do.

Why can’t I shed a single tear, Dad? Am I a man or a rock? Tell me – why is it like this?“

The candle looked at him in surprise, pondered, then crackled a few times – but drew upwards and burned more steadily.

He sighed with relief.

„Phew, I was already starting to think you’d scold me. You’ve probably forgotten, but I remember how I asked you as a kid why you never cried, and you always said, ‘Because I’m Dad.’ Only later did you tell me that you cry too, sometimes – but secretly. Only I can’t, not even secretly, Dad. I’m terribly ashamed, I try, but it just won’t come. I don’t know what I’ll do tomorrow, when people gather. Is that even normal, Dad?“

He got up and closed the door to the terrace. The old house was beginning to stir, creaking and coughing, perhaps scratching itself in the places one scratches in the morning… From downstairs there were already noises – doors banging, the smell of cooking wafting up.

„Alright, Dad, I’ll leave you now. I need to tidy myself up a bit – I look like a guerrilla fighter. And people will want to see me – a live bear come from Berlin… Right then, you rest.“

***

A miserable drizzle was falling, a merciless wind whipped across the cemetery, and Father Stayko spent the entire time pressing down his clerical cap, even as he tried to read diligently – his brother had slipped him a little extra to awaken at least some enthusiasm in the priest. His red, rakia-drinker’s nose was dripping, the old man blew his nose in bass tones into a large chequered handkerchief and continued to read, patiently listing the endless names from the document prepared by some careful relative. Probably Uncle Dimcho – he was the only one who knew the family history.

The lunch passed efficiently, without unnecessary interruptions. „Thank God they don’t have the habit here of giving endless speeches,“ he thought, while sipping another rakia – smooth, but strong, like the people around here. If you don’t keep an eye on it…

His brother sat beside him – had already cried his fill, now looked visibly relieved, even diving into long, tangled, hesitant explanations with a cousin he hadn’t spoken to in years. His mother was too busy flitting about, making sure everything was in order – her black mourning scarf had slipped to reveal her still well-preserved hair. From time to time, the mirror across from him would show a face contorted in a spasmodic twitch, all eyes because of the dark circles, and he would quickly look away in shame. No, not a trace of moisture. Dry, fixed, frozen eyes.

Evening came with a sagging belly – the day had slipped by like a thin wisp of smoke, unnoticed. At home, the rituals continued – another table spread, this time only for the closest family, again heavy faces, gradually lightened by the gentle palm of the rakia. He sat with everyone, not even passively – even passionately, whenever someone began to tell one of his father’s endless stories…

„So old Mitko had bought two watermelons, big ones, ten kilos each, and since he didn’t feel like bending all the way to the back seat, he tossed them up front beside him – but they were so big, and the space so small – and just as he’s chugging up the hill in the Trabant, suddenly, out of nowhere, the side door opens and the watermelons go bouncing down the slope. Old Mitko is swearing his lungs out – you all know what a roar he had – but the watermelons don’t care, they’re tumbling and bouncing down the cobbles like they think they’ll get away with it. And from below here comes Bodurov, dressed in his newest suit – it must’ve been some holiday. And he shouts up, ‘Enev, don’t worry, I’ll catch them both!’ Fine, but right then one of those watermelons hits a blind cobblestone, bounces, explodes into a hundred pieces and – splat – straight on top of Bodurov, new suit and all. One’s swearing from below, the other from above – a full-on concert, like cats in spring. They didn’t talk for two months after that.“

The group tried to hold it in, strained to stay serious as the occasion demanded, but finally gave in and started humming with laughter, like a bagpipe’s rumble. He too caught himself shaking uncontrollably, even though he knew the story by heart – nothing in it was made up, and it had long since become an inseparable part of the folklore of the small town, hungry for a bit of relief like any provincial nest.

„Oh, and the other one, when they were combine drivers once. With Lambov, you remember? Wait now, this one’s even better. So they go off on contract – combine drivers got paid well, and there was always need for volunteers in summer, plus the co-op gave free meals. So our two heroes sit down in the canteen – the cook Andrey was one of their own – and, believe it or not, they eat an entire tray of meatballs. Stuffed themselves like balloons, couldn’t even bend down to tie their shoes, but since they’re drivers, they head back to the field in the afternoon. Alright, but Lambov at one point feels his stomach squeeze up, stops the combine near a walnut tree and says to our guy, ‘Enev, I’m going back – got a bit of a situation.’ Ten minutes, twenty, half an hour – the guy’s gone. So old Mitko goes looking – and what does he find? Lambov squatting there, hadn’t noticed his apron was caught underneath him, and ended up doing all his business right on it – like on a doormat. And you know him, he was a hundred and thirty kilos, so his output wasn’t exactly small either – tries to get up, can’t, no way! The apron’s stuck under the weight, won’t let him rise – and that’s it! And he’s too embarrassed to call for help, just crouches there waiting for it to dry so it gets lighter. What are you laughing at? I’m telling you the God’s honest truth – later they scraped that apron for two hours with bare cobs till it looked like something again.“

„Oh, that’s nothing. Remember the time they went fishing out of season, and Angel, out of fear, hooked his own lip in the dark… then they had to wake up Doctor Marchev in the middle of the night — and ended up plastered all over the town paper, with a fine on top…“

And this one… and that one… The stories flew one after the other – spicier, twistier. Hearts loosened, faces flushed. And right then something sliced through him from inside – his stomach clenched, he barely managed to hide his face in his hands and convulsed, powerless to resist the storm forcing its way out through his eyes. The others froze, fell silent. His brother led him – almost carried him – into the next room, but the evening was already ruined, and soon after everyone hurried to say goodbye, with embarrassed, shrunken faces.

Only the dead man kept laughing, perfectly pleased with how it had all turned out, somewhere from above.

Later that night, already in the deep hours, he woke up, turned over the drenched, soaked pillow, and whispered sleepily:

„Thank you, Dad. Thank you so much.“

And fell asleep again – deep and peaceful.