Most

Recent

Read

Commented

Politics and Society

When Collective Pathos Collides with Personal Memory

I want to begin with a story I would rather not recall too often. It was 1984. I was twenty-three, a philosophy student in the capital, travelling back to Preslav for one of the holidays. I was weighed down by a tangle of thoughts that felt literally impossible to share. The so-called “Revival Process” had begun shortly before. A small, sleepy provincial country had suddenly, within the span of just a few months, turned into something dark and threatening. Police officers stopped me in the streets to check my papers, because a young man with a shaved head must have looked to them like a potential terrorist. Things like that.

I came home. My father was a man I have always described in the same way: the best, most loving father I could imagine. A good man with a gentle disposition, the sun of my childhood. We sat down to talk, and he began to explain to me, calmly, almost tenderly, that what the state was doing to the Turks was right. That “otherwise they will swallow us,” because they had many children. That the country was Bulgarian and they had to become Bulgarians.

“Don’t get angry, my boy. We’re doing what must be done.”

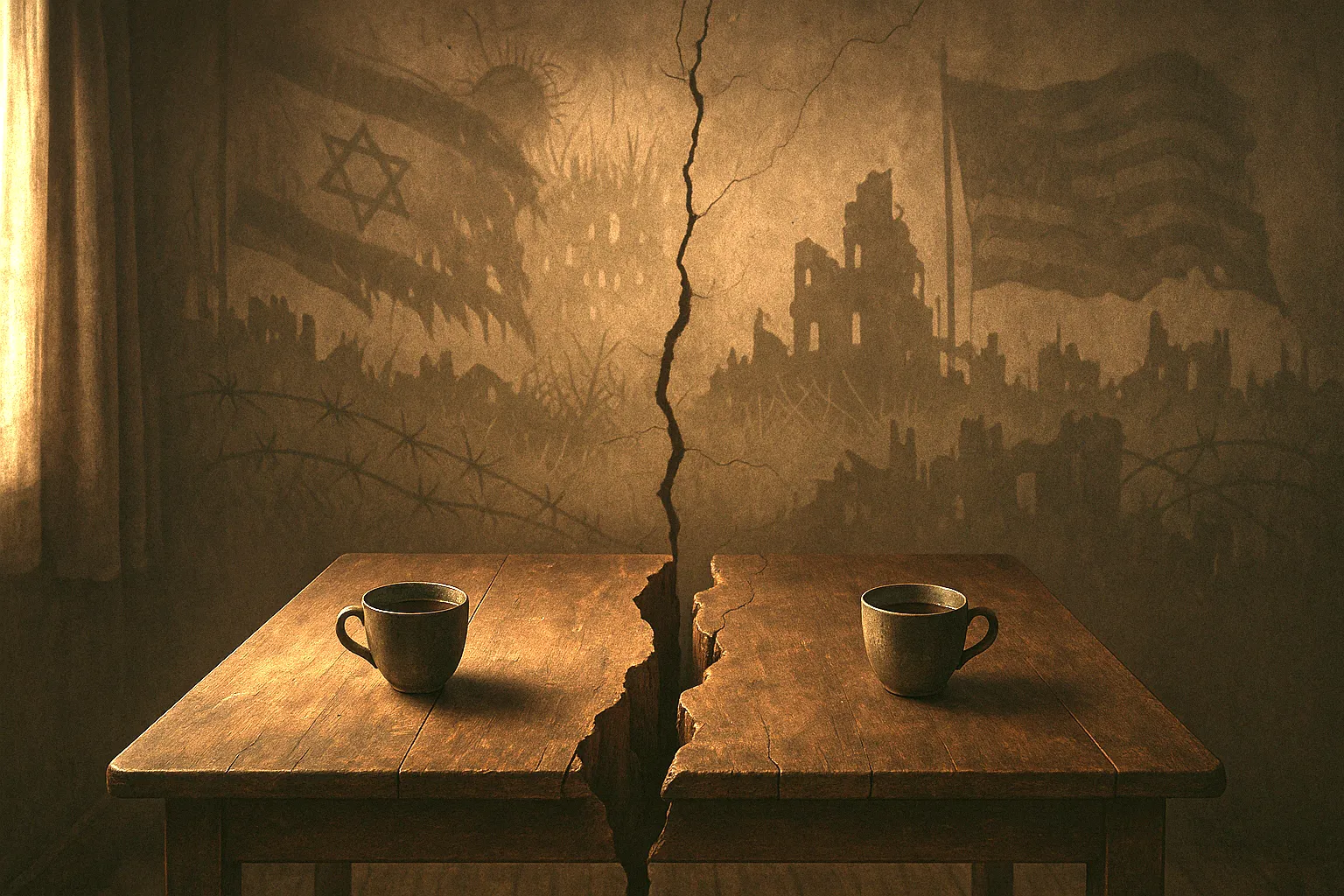

I looked at him and did not know what to say, how to react. I could not reconcile within myself the man I had been used to loving unconditionally with the man who was speaking these words. It was the first time I felt, not abstractly but almost physically, how a collective madness can enter your home, sit down at the table, and begin to explain to you that it is doing something good.

Perhaps that is where this somewhat strange allergy of mine comes from. An allergy to the hysterical certainty that “our people” are right simply because they are ours. To the sweet pathos with which a majority explains its own cruelties as historical necessity, as “taking back what was done to us.” To the heroic songs with which we try to drown out someone else’s cry.

With that same allergy, I now look at the way the Bulgarian conversation about Gaza and Israel has been unfolding for more than a year.

The Two “Churches” of Bulgarian Facebook

When Gaza and Israel come up on Bulgarian Facebook, I almost hear the melody before I read the text. The division is clear, the camps are already arranged, the moral topography mapped out in advance.

One group sees almost exclusively the Palestinians. They are cast as the heirs of all the oppressed in history, the last of the colonized, the condensed pain of the Global South. From this perspective, Israel appears as a pure monster: a colonial fortress, a Western outpost, an armed-to-the-teeth machine of destruction. Everything is clear and simple, the roles distributed like in a classical operatic script: victims and executioners, oppressed and oppressors. Viewed through the didactic lens of our national literary and historical canon, Gaza becomes the new Shipka Pass of global justice.

The other group sees almost exclusively Israel. A small democracy surrounded by hostile regimes, a state that from its first day has defended itself with its back pressed against the wall. Palestinians dissolve into a faceless mass of “terrorists” who do not understand “our civilizational values” and prevent normal people from living normal lives. Here too everything is clear: Israel is “our” small hero, holding the line against barbarism.

The flags differ, but the gestures are the same. In both cases, Bulgarians step into a familiar role. Once again they are on the side of the “small and righteous people,” once again they wave flags, once again they intoxicate themselves with words about history, destiny, and eternal justice. Only this time the terrain is not the Balkan Mountains but the Middle East.

At first glance, this looks like solidarity. At a second, like projection. At third, like the use of someone else’s tragedy in order to sing our own old refrains.

Old Wine in New Skins

We Bulgarians have developed a crude but effective technology for turning history into mythology. Already at school we are initiated into the world of “slavery,” “heroes,” “the cause,” “the feat.” In the grand narrative there is almost no room for grey. As a rule, figures and realities such as collaborators, cowards, greedy revolutionaries, or Balkan petty-mindedness are absent. The past is presented to us only after it has been carefully filtered through a black-and-white sieve.

This matrix is so strong that when a new conflict is thrown at us, we automatically ask not “What is specific here?” but “Who are our people here?” Who are “we” in this film?

Palestinians easily slip into the role of a national liberation movement, Israel into the role of a state that “defends its land.” Depending on our political taste, we readily jump from one identification to the other, but almost always within the same old spectacle: the revolutionary opera of the nineteenth century.

The difference is that today heroism is staged on social media rather than on the peaks of the Balkan range. Today’s amplifier is the smartphone, not Botev’s notebook. But the logic remains the same: we need a plot in which we stand on the right side.

Where My Allergy Comes From

I live with the self-awareness of someone who arrived at this distrust not primarily, or not only, through abstract theory. I have seen up close how myth can be used as an instrument of governance. I have seen in real time how “historical justice” was invoked to justify name changes, broken lives, expulsions, mass violence, both physical and psychic. I have seen how an entire “population” can whisper to itself, with fanatical tenderness: “This is the right thing to do. Otherwise they will swallow us.”

That is why today, when I hear people speak about Gaza and Israel in the same tone once used to justify the “Revival Process,” it does not strike me as merely wrong. It tightens my throat.

I cannot accept Israel’s current military conduct: the systematic bombardments, the destruction of entire neighborhoods, collective punishment, the language of “self-defense” functioning as a blank cheque for everything. I cannot accept how a real trauma such as the Holocaust is turned into a moral shield behind which other crimes can be hidden, crimes committed against people who had nothing to do with gas chambers.

But just as clearly, I cannot accept the romanticization of October 7 as a “return home,” as Salman Abu Sitta does, for example, one of the latest authors I nevertheless presented in my magazine. When armed men enter settlements and a music festival, kill civilians, and take hostages, this is not a “return home.” It is mass violence. We are obliged not to close our eyes to the history that produced it: occupation, despair, blockade, decades of relentless humiliation. But we cannot change the name of what happened depending on which camp we consider “ours.”

Here my allergy is triggered once again. Every time violence against civilians is renamed an “act of resistance” or “inevitable self-defense,” I hear not an argument but the monotonous beating of a drum. The same drum that entered my own home in 1984 and made me look at my father with horror.

Why I Refuse to Take “A Side”

In our context, refusing to “take a side” is often perceived almost as a moral defect. If you are not clearly and loudly aligned with one camp, you must be either with the other or spineless, some kind of “liberal hypocrite”.

I am not neutral about what is happening. Quite concretely, I oppose the killing of civilians, regardless of who is holding the weapon. I oppose state terror when it is presented as a fight against terrorism. I oppose the romanticization of brutality in the name of any cause. I oppose turning history into an ammunition depot for future wars.

It is precisely for these reasons that I cannot place myself under the banner of “absolute Palestinian righteousness”, which absorbs inconvenient facts without remainder: corruption, internal repression, the crushing of political alternatives, the passive role of local Arab regimes. Nor can I place myself under the banner of “absolute Israeli righteousness”, which sees every Palestinian as a potential threat, every criticism as antisemitism, and every bomb as an inevitable security measure.

If this means standing between two chairs and choosing the floor, so be it. Better to sit on the floor than to have my voice used as part of a choir whose refrain makes my skin crawl.

Bulgarian Megaphones for Other People’s Wars

The saddest thing about the Bulgarian conversation on Gaza and Israel is that it is rarely actually about Gaza and Israel.

Pro-Israeli voices often speak in a language learned from foreign think tanks: “civilization versus barbarism”, “the West versus terror”. Pro-Palestinian voices often repeat the vocabulary of American university campuses: “colonialism”, “white power structures”, “liberation struggle”. Both sides rarely rest on solid knowledge of the conflict itself, of internal Palestinian divisions, of internal Israeli fractures, or of the details of international law.

Much more often, something else is taking place: the projection of Bulgarian anxieties and fantasies onto a foreign screen.

The pro-Palestinian Bulgarian often sees in the Palestinians our own revolutionary ideal: a small, proud, crushed people rising against an Empire. In this way, often unconsciously, he or she compensates for a sense of powerlessness here and now.

The pro-Israeli Bulgarian often sees in Israel the imagined “strong, normal Western society” that guards its borders, does not hesitate in the face of threats, and is willing to use force. In this way, he or she compensates for helplessness in the face of corruption and chaos at home.

As a result, real people in Gaza and Israel, alive and dead, mutilated and displaced, are reduced to raw material for our internal dramas. Someone else’s war, old wine, new skins.

What Actually Interests Me

Someone might ask: “If you are neither here nor there, then what do you believe in? Some comfortable, colorless center?”

No. I do not believe in the possibility of a comfortable center. What interests me is something much simpler and much harder.

I am interested in the possibility that facts are not repainted according to the flag we happen to be standing under today. I am interested in the necessity that legal concepts such as war crimes, genocide, and occupation are not used as convenient labels for things we only vaguely understand. I am interested in the imperative that human life should not be valued differently depending on whether it is Jewish or Arab, “ours” or “theirs”. I am interested in the obvious truth that political positions must not turn into religions in which doubt is treated as sin.

If there is anything I would put my name under, it is the right to be repelled by more than one injustice at the same time. The right to say “this is a crime” without automatically entering someone’s list of “our people”. The right to refuse to call killing “return”, or the systematic destruction of an entire city “necessary self-defense”.

A Small Personal Oath Amid the Noise

We live in an age in which every public sentence must function as a marker of belonging. Say something against Israeli policy and you are immediately assigned to the “Palestinian camp”. Say something against Hamas and you are sent to the “Zionist camp”. There is no intermediate space.

But I know one thing. I have lived long enough in a culture that divided people into “correct” and “incorrect”. What I learned is that I must never again allow myself to wear any uniform whatsoever, military, moral, or simply clownish.

What I can promise myself is relatively modest. Not to use other people’s dead and wounded to decorate my own political passions. Not to call “historical necessity” something I find morally unacceptable. Not to participate in mythologies, Bulgarian, Israeli, Palestinian, or “Western”. To continue to doubt, both “ours” and “theirs”, and my own sense of righteousness.

I do not claim this is a heroic position. I see it rather as an attempt to keep a healthy distance from a world that is more in love with its causes than with living people.

In a small and until recently isolated country, built on myths of enslavement and heroic uprisings, it is almost natural to fall in love with the next liberation drama, today Gaza, tomorrow somewhere else. I simply choose not to fall in love. To watch, to name things, to remain silent when I do not know, and to refuse participation when I am asked to become part of a choir whose song I have already heard at least once in my life.

I watch the news, read the Facebook quarrels, and simply tell myself: no, I will not sing this.

Never again.